Deploying Docker containers to GKE using Terraform + Terragrunt

July 23, 2020

So, you've built your platform, you've got some lovely microservices, and now you'd like to deploy your infrastructure with Terraform. Why do I even care about infrastructure as code, you ask? A story will always explain it best.

As an added bonus, you'd love for it to deploy to a development environment when code is pushed to the develop branch, and to production when pushed to master, as part of a GitOps approach.

Let's look at how we can do this, and keep our code DRY with Terragrunt. We'll look at deploying the following:

- Google Cloud Project per environment

- Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE)

- Docker images onto Google Kubernetes Engine

- A database provisioned by Google Cloud SQL

We're also going to assume that we'd like to run our development environment in a cheaper (and therefore different) region, and with less nodes in our GKE cluster, so we need to be able to configure some of these parameters on a per-environment basis.

Let's get started. Exemplar code is available on GitHub.

Prerequisites

Install the following to get started.

- Docker

- Google Cloud Platform account with billing enabled

- Terraform

- Terragrunt

- Kubectl

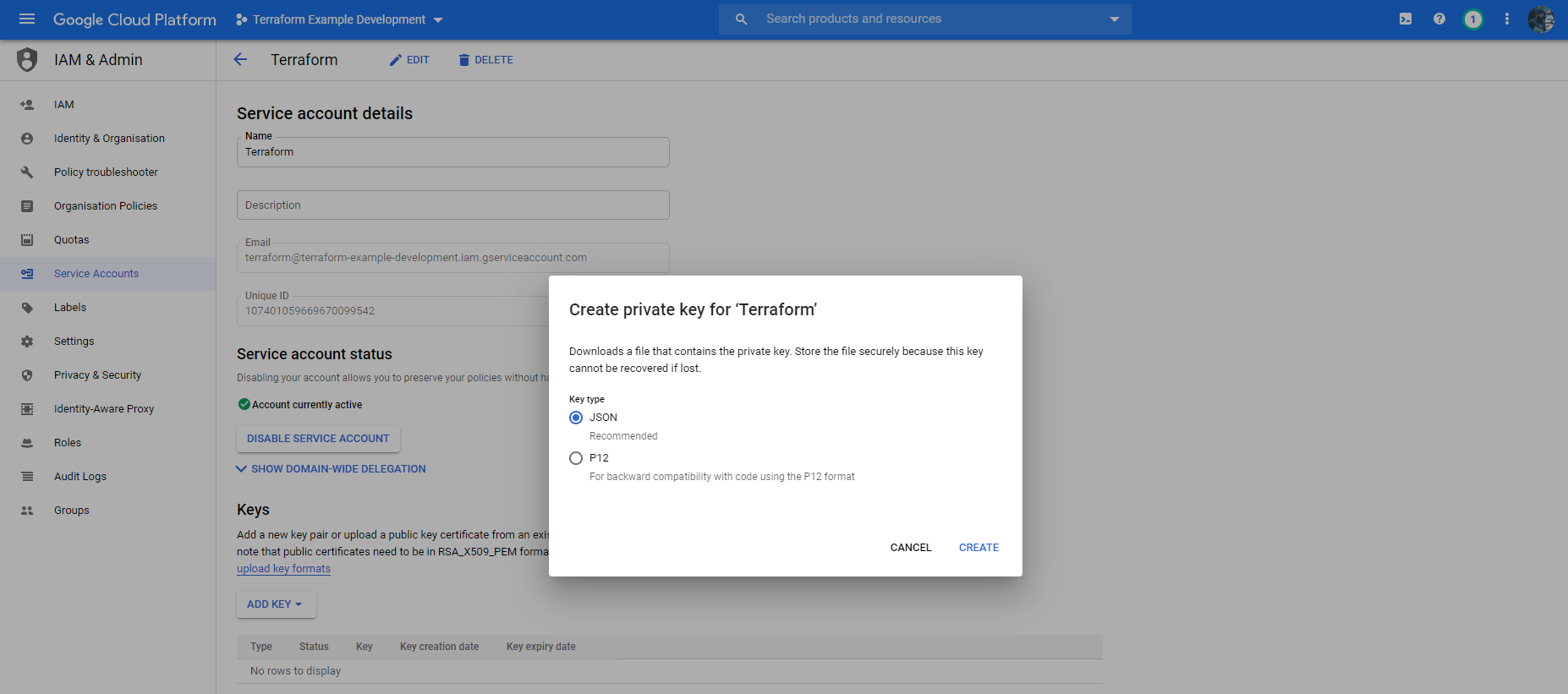

Now, create two projects with Google Console, named anything. One will be used for development deployments, and another, production deployments. Create a service account for each project, with Editor access. Once a service account is created, you can create a key for the service account (choose JSON), and download these. Keep them safe, we will need these.

CAVEAT

There is one more manual step involved - you must enable the Cloud Resource API manually for your projects. I did try to define a Terraform step which automatically enables the correct permissions, however it ironically requires the Cloud Resource Manager API enabled first to do this.

If anyone has a better suggestion, let me know in the comments!

Structure

It's recommended to create a separate folder for all terraform/infrastructure needs at the root of your application. I will unsurprisingly designate this to be named terraform.

mkdir terraformNow we're almost done! (No, do keep reading)

The remaining structure that this example uses is based off Terragrunt's example and Jake Morisson's post.

We'll create two folders:

- modules - Isolated Terraform modules for repeatable instances of infrastructure: databases, services, load balancers.

-

live - Terragrunt declarations of our actual infrastructure, leveraging the modules we define. Create folders to hold the declarations for any different environments inside:

- development

- production

The development and production folders will contain sub-directories corresponding to each unit of infrastructure. These folders will call upon any of our modules that we define.

An example: live/production/gcp-gke will provide the specific parameters required by modules/gcp-gke. This means that we can configure a different live/development/gcp-gke unit for our development environment, but only need to change the variables we pass.

We will place .hcl files in the corresponding environment directories, which will contain environment-specific shared variables across the services. E.g. live/development/env.hcl will contain our development Google Account details.

Now we're DRY-ing ✔.

What does Terragrunt do for us?

A lot of the original USPs that Terragrunt boasts are slowly making their way into Terraform. But that still leaves a few worthwhile reasons to pick it up.

Terragrunt can read and include these files, so that we can keep them in one place. We can now include other .hcl files with the include block and cleanly represent dependencies with the dependency block. More information on the extensions that Terragrunt provides is available via the Terragrunt Docs.

When we run terragrunt apply-all, it will find all terragrunt.hcl files in all sub-folders and execute them. So, to deploy production infrastructure, all we now need to do is cd production && terragrunt apply-all. Can you do this with Terraform, you ask? Well, yes, by defining various variable files and supplying CLI arguments. This approach becomes cumbersome on a day-to-day basis. This Reddit post provides a good example of this.

Enough talk, show me the money!

So far, we have:

- terraform/

- live/

- development/

- production/

- modules/We are going to work towards ending up with:

- terraform/

- live/ <= Our actual infrastructure

- common.hcl <= Common variables that apply across environments

- terragrunt.hcl <= Common parameterised, declarations for state storage etc, used by children files

- development/

- credentials.json <= Development Project's Google Service Account credentials

- env.hcl <= Variables for development environment

- gcp-gke/

- terragrunt.hcl <= Includes env files and supplies values to corresponding module

- gcp-sql/

- terragrunt.hcl

- production/

- credentials.json <= Production Project's Google Service Account credentials

- env.hcl <= Variables for production environment

- gcp-gke/

- terragrunt.hcl

- gcp-sql/

- terragrunt.hcl

- modules/ <= Reused by live/

- gcp-gke/

- main.tf <= Declarations

- variables.tf <= Module's input variables

- output.tf <= Module's output variables

- gcp-sql/

- main.tf

- variables.tf

- output.tfGo ahead and create these directories.

Although you may see a duplication of structure, do remember that modules/gcp-gke specifies how to create a Google Kubernetes Cluster, whilst development/gcp-gke will leverage modules/gcp-gke to create a Google Kubernetes Cluster for the development environment with the supplied configuration.

Service Account Credentials

For now, place the two service accounts that you created earlier into the corresponding directories. You should never commit these to a repository. Instead, the contents should be supplied as an environment variable by CI and written to disk during the execution of pipeline, or a secrets manager should decode the files during the pipeline run.

common.hcl: Cross-environment shared variables

This file will contain variables that we want to share across all our environments. Currently, this will include simply the organisation name, which will be used elsewhere.

# terraform/live/common.hcl

locals {

# Global organisation identifier

org = "terraform-rabit-pig"

}The locals block is Terraform syntax defines variables that can be used elsewhere within the file.

terragrunt.hcl: Root Terragrunt file

terraform/live/terragrunt.hcl will contain the common elements that we'd like to merge with our actual infrastructure declaration files.

Let's start by reading in any variables we might need.

locals {

# Load any configured variables

env = read_terragrunt_config(find_in_parent_folders("env.hcl")).locals

common = read_terragrunt_config(find_in_parent_folders("common.hcl")).locals

}You may have noticed that we haven't defined env.hcl yet. This is because it'll reside in each environment's directory (terraform/live/production or development).

find_in_parent_folders("env.hcl") may not make sense in this context, but if you remember that the root terragrunt.hcl file will be included by other files, then this now makes sense.

It's time to configure remote state. Terraform needs to store the state of the infrastructure somewhere. It can be done within your Git repository, but it's highly recommended to use remote storage. In our case, we will use a Google Cloud Storage bucket for this:

# Configure Terragrunt to store state in GCP buckets

remote_state {

backend = "gcs"

config = {

bucket = join("-", [local.common.org, local.env.env, "--terraform-state"])

prefix = "${path_relative_to_include()}"

credentials = local.env.credentials_path

location = local.env.region

project = local.env.project

}

generate = {

path = "backend.tf"

if_exists = "overwrite_terragrunt"

}

}This instructs Terragrunt to generate a backend.tf file with all modules. To show you the output from the Terragrunt cache:

# Terragrunt cache output: backend.tf

# Generated by Terragrunt. Sig: nIlQXj57tbuaRZEa

terraform {

backend "gcs" {

credentials = "D:/Projects/terraform-example/terraform/live/development/credentials.json"

prefix = "development/gcp-gke"

bucket = "terraform-rabit-pig-development---terraform-state"

}

}Our modules will require a Provider, which is responsible for understanding interactions and exposing resources. Now, let's add a common provider configuration for Google Cloud Platform:

generate "provider" {

path = "provider.tf"

if_exists = "overwrite_terragrunt"

contents = <<EOF

provider "google" {

version = "~> 3.16.0"

credentials = "${local.env.credentials_path}"

project = "${local.env.project}"

region = "${local.env.region}"

}

# For access to Google Beta features

provider "google-beta" {

credentials = "${local.env.credentials_path}"

project = "${local.env.project}"

region = "${local.env.region}"

}

EOF

}All configuration options are available on the Google Cloud Platform Provider documentation page. Like backend.tf, Terragrunt will generate provider.tf and place this in the folder of any module that includes the root terragrunt.hcl.

Finally, we'll configure some convenience inputs that will be merged with and available to any other Terragrunt modules that include this file:

inputs = merge(

local.env,

local.common,

)We're now done with defining our reusable terraform/live/terragrunt.hcl file.

env.hcl: Environment-specific variables

We'll define two files:

terraform/live/production/env.hclterraform/live/development/env.hcl

This will allow us to satisfy one of our earlier requirements of different configurations and regions per environment.

Add the following to each file:

locals {

env = "development"

region = "us-east1"

credentials_path = "${get_terragrunt_dir()}/credentials.json"

credentials = jsondecode(file(local.credentials_path))

service_account = local.credentials.client_email

project = local.credentials.project_id

}Note how the project identifier and service account email address are extracted from the credentials, for our own convenience.

Defining Modules

We've defined some reusable configuration in the live directory, but now it's time to actually define the Terraform modules that will be doing the work, inside terraform/modules.

Let's start with Google Kubernetes Engine. We'll make use of the Google's GKE module.

There's 3 tasks to complete to successfully spin up a GKE cluster:

- Enable the correct Cloud API features

- Create a Network VPC

- Create a GKE cluster using the VPC defined in 2)

Inside terraform/modules/gcp-gke/variables.tf, specify the input variables to the module:

variable "project_id" {

description = "The project ID to host the cluster in"

type = string

}

variable "cluster_name" {

description = "The name for the GKE cluster"

}

variable "region" {

description = "The region to host the cluster in"

type = string

}

variable "zones" {

description = "The zones to host the cluster in"

type = list(string)

}

variable "machine_type" {

description = "The machine type for nodes in the node pool"

type = string

}

variable "min_nodes" {

description = "The minimum number of nodes in the node pool"

default = 1

type = number

}

variable "max_nodes" {

description = "The maximum number of nodes in the node pool"

type = number

}

variable "disk_type" {

description = "The type of disk"

type = string

default = "pd-standard"

}

variable "disk_size" {

description = "The size of each node's disk (GB)"

type = number

default = 100

}

variable "preemptible" {

description = "Whether nodes are premptible or not"

type = bool

default = false

}These can all be referenced by var.NAME. E.g: var.premptible.

We can define the content of the module now. Create terraform/modules/gcp-gke/main.tf and start by defining some reusable local variables:

locals {

network = "${var.cluster_name}-gke-network"

subnet = "${var.cluster_name}-gke-subnet"

ip_range_pods = "${var.cluster_name}-gke-pods"

ip_range_services = "${var.cluster_name}-gke-services"

}These variables hold network-related names, which will be used more than once.

Add a block to enable the APIs required:

# Enable required account services

module "gcp_services" {

source = "terraform-google-modules/project-factory/google//modules/project_services"

version = "~> 4.0"

project_id = var.project_id

disable_services_on_destroy = false

disable_dependent_services = false

activate_apis = [

"iam.googleapis.com",

"compute.googleapis.com",

"container.googleapis.com",

]

}It's time to create a network:

# Add a network

module "gcp_network" {

source = "terraform-google-modules/network/google"

version = "~> 2.4"

project_id = module.gcp_services.project_id

network_name = local.network

subnets = [

{

subnet_name = local.subnet

subnet_ip = "10.0.0.0/17"

subnet_region = var.region

},

]

secondary_ranges = {

"${local.subnet}" = [

{

range_name = local.ip_range_pods

ip_cidr_range = "192.168.0.0/18"

},

{

range_name = local.ip_range_services

ip_cidr_range = "192.168.64.0/18"

},

]

}

}Note how project_id = module.gcp_services.project_id. You may wonder why we don't simply use var.project_id. Well, there's a good reason for it: Terraform will attempt to figure out the dependencies between different resources, and consequently execute sequentially or in parallel as appropriate. By using module.gcp_services.project_id, we are telling Terraform to wait until module.gcp_services.project_id is available. Without this, the next steps would fail, as relevant the Cloud APIs may not have been enabled.

The next step is to actually spin up the cluster:

# Build a zonal cluster

module "gke" {

source = "terraform-google-modules/kubernetes-engine/google"

version = "~> 10.0"

project_id = module.gcp_network.project_id

name = var.cluster_name

region = var.region

regional = false

zones = var.zones

network = local.network

subnetwork = local.subnet

network_policy = false

ip_range_pods = local.ip_range_pods

ip_range_services = local.ip_range_services

create_service_account = false

horizontal_pod_autoscaling = true

remove_default_node_pool = true

node_pools = [

{

name = "gke-pool"

machine_type = var.machine_type

preemptible = var.preemptible

initial_node_count = var.min_nodes

min_count = var.min_nodes

max_count = var.max_nodes

disk_type = var.disk_type

disk_size_gb = var.disk_size

auto_upgrade = true

}

]

}It's very convenient to configure the defaults appropriate for your system, and expose anything that varies as, well, variables.

We've forgotten one thing - define some outputs! This will allow other modules to access useful information - if we'd like to deploy to the cluster, we need to be able to authenticate with it, and so we must export that information from this module, in outputs.tf:

output "cluster_endpoint" {

description = "The IP address of the cluster master"

sensitive = true

value = module.gke.endpoint

}

output "cluster_name" {

description = "The name of the cluster master"

sensitive = true

value = module.gke.name

}

output "ca_certificate" {

description = "The public certificate that is the root of trust for the cluster"

sensitive = true

value = module.gke.ca_certificate

}

output "access_token" {

description = "The access token to authenticate with the cluster"

sensitive = true

value = data.google_client_config.default.access_token

}

output "network_name" {

description = "The name of the VPC being created"

value = module.gcp_network.network_name

}

output "subnet_name" {

description = "The name of the subnet being created"

value = module.gcp_network.subnets_names

}

output "subnet_secondary_ranges" {

description = "The secondary ranges associated with the subnet"

value = module.gcp_network.subnets_secondary_ranges

}We have a module that only exposes the aspects of spinning up a GKE cluster that we are interested in.

Calling our modules with Terragrunt

We're done with defining our own Google Kubernetes Engine module, but how do we supply variables to it and spin it up?

This is where our terraform/live/[env]/[module]/terragrunt.hcl files come in.

Inside terraform/live/development/gcp-gke/terragrunt.hcl, let's define the cluster we'd like.

The first thing to add is an include block:

include {

path = find_in_parent_folders()

}find_in_parent_folders(), without parameters, looks for any parent terragrunt.hcl files. Fortunately, we defined a root terragrunt.hcl file, which contains our provider and remote backend configuration.

How do we tell Terragrunt which Terraform module we'd like to use?

terraform {

source = "../../../modules/gcp-gke"

}The next thing to do is actually specify the inputs for our module, and any locals we need alongside:

locals {

env = read_terragrunt_config(find_in_parent_folders("env.hcl")).locals

common = read_terragrunt_config(find_in_parent_folders("common.hcl")).locals

}

inputs = {

project_id = local.env.project

cluster_name = join("-", [local.common.org, local.env.env])

region = local.env.region

zones = ["us-east1-b"]

machine_type = "n1-standard-1"

max_nodes = 2

disk_size = 10

preemptible = true

}And voila! If we wanted a second cluster, you would duplicate this into another file and change the parameters as appropriate.

In fact, you'll have to do this for the production folder, which I leave as an exercise to the reader.

Deploying my live configuration

You've defined all of your infrastructure, and now you're ready to hit run!

Terragrunt provides a terragrunt plan-all to view the changes that will be made, and terragrunt apply-all to actually apply them. This is identical to the terraform plan and apply commands, instead running them in each directory.

You can now cd terraform/live/development and run terragrunt apply-all to pull up your development infrastructure, and similarly for production.

It's that simple.

What about Cloud SQL & deploying Docker images? You promised!

True. But I think this post is too long already. Remember, I'm new to this!

Instead, check out the example repository that I created, which applies the same principles outlined in this post to spin up a Cloud SQL instance and also deploys an NGINX image on port 8080.

Though, if anyone would like a follow-up post on getting these other components running, let me know!